19

Get started with type hints in Python

Type hints help you make your Python code more explicit about the types of the things you're working with. They've been a huge productivity booster for me. If you're familiar with basic Python — control flow, functions, classes — this will bring you up to speed in no time.

Python is dynamically typed. It means that at the time of writing a program, you generally don't know what type a variable (or other expression) will be:

def double(x):

return x + xHere you don't know what type x will take.

Dynamic typing doesn't rid you of types. It just moves the responsibility of matching them onto the programmer.

Keeping track of types yourself isn't always bad. It lets you express flexible relations, perhaps something you can't do in C++ or Java. Dynamic typing has its own patterns, such as duck typing.

However, most of your functions have simple contracts. If you keep them implicit or informal (say, in a comment), you can't analyse them with tooling. A compiler that guides and corrects you is a big selling point for languages with rich type systems, like Haskell and Rust.

Last but not least, having a standard way of expressing contracts makes code easier to understand.

Python allows you to document types with type hints. They look like this:

def double(x: int) -> int:

return x + xThe x: int part means that the function expects an int object to be passed to the function; and the -> int means that the function will return an int object.

A tool like mypy or pyright can now check that you're not doing something shady, like here:

def double(x: int) -> int:

return x + "FizzBuzz" # error!The types aren't checked at runtime, though — when you run the Python script, the interpreter doesn't care about type hints.

The interpreter doesn't do any optimizations based on annotations. Again, only programmers and type-checking tools give them meaning.

Python embraces what's called "gradual typing". You can typehint only part of your code and leave some parts untyped (as before), for example if they're impossible or very hard to annotate.

PyCharm already has its own custom type checker.

You can install mypy — one of the tools that does type checking — by following the instructions here;

Pyright (which is the tool I personally prefer) can be installed here.

If you're using Visual Studio Code, you can install the Pylance extension which uses Pyright for typechecking.

First, you can put them on an individual variable:

answer: int = 42Most of the times it's redundant. Type checkers know that 42 is an int.

Type hints are useful on functions, to explain what the function takes as input and what it returns:

def double(x: int) -> int:

return x + x

def print(*args: Any, end: str = " ") -> None:

......and on class attributes, to explain the types of objects stored in those attributes.

class Point:

x: int

y: intWhen you're assigning something to a variable, the type checker (remember — just a tool, separate from Python) will infer the type of the variable.

![numbers = [1, 2, 3] inferred as list[int]](https://res.cloudinary.com/practicaldev/image/fetch/s--tkWQ6PuG--/c_limit%2Cf_auto%2Cfl_progressive%2Cq_auto%2Cw_880/https://dev-to-uploads.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/articles/6uspj39rvpvq0pocj1my.png)

Inference is not "guessing" as the name may suggest. A more correct synonym would be deduction — figuring the type precisely by following an algorithm.

All the types you're familiar with — int, str, float, range, list etc. — are valid type hints.

The typing module provides some more sophisticated type hints.

Sometimes you don't want to specify a type:

- You can't express it in the Python's type hint system;

- It would be verbose and confusing, requiring lots of extra code;

- You really don't care what the type is — consider the

printfunction.

Any denotes the "wildcard type". It can be treated as any type, and any value can be treated as Any.

from typing import Any

def print_twice(something: Any) -> None:

print(something, something, "!")(note: you may not have to write the -> None here — Pyright [and mypy if you set the appropriate option] will infer it for you)

Don't overuse Any, though — there are often better ways.

Sometimes you accept several types, not just one!

# str OR int --V

def print_thing(thing: ???) -> None:

if isinstance(thing, str):

print("string", thing)

else:

print("number", thing)In that case, you can use typing.Union.

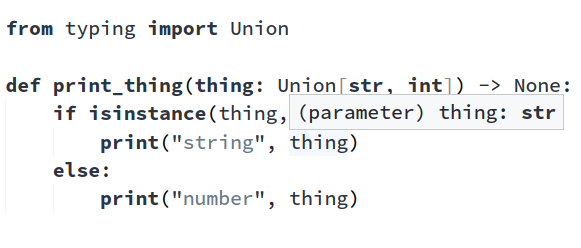

from typing import Union

def print_thing(thing: Union[str, int]) -> None:

if isinstance(thing, str):

print("string", thing)

else:

print("number", thing)Unions are very powerful. Type checkers can do what's called type narrowing: an if or a while condition can restrict the type. For example, type checkers understand isinstance checks:

It means that you can do this:

def print_thing(thing: Union[str, int]) -> None:

if isinstance(thing, str):

print("string", thing + "!")

else:

print("number", thing + 10)and the type checker will understand that in the first if clause thing has type str, and in the second clause it has type int.

Here we've seen that some types can be parametrized — you can pass arguments to a type to configure it. It's not special syntax — it's just using subscription, like you do on lists and dictionaries.

Optional[YourType] is just a shorthand for Union[YourType, None]. Union with None is very commonly used to indicate a potentially missing result. For example, when you call .get(some_key) on a dictionary, you get either an item or None.

Let's typehint this function that implements translation from Russian to English, but caches the results. It will encode an unknown word as None.

from typing import Optional

_cache = {"питон": "python"}

def translate(word: str) -> Optional[str]:

from_cache = _cache.get(word)

if from_cache is not None:

return from_cache

fetched = fetch_translation(word, "ru", "en")

if fetched is None:

return None

_cache[word] = fetched

return fetchedTry to assign a type to every variable in the snippet.

(Answer:

word: str

from_cache: Optional[str] (or Union[str, None])

(but after the first if it's str, because of narrowing)

fetched: Optional[str] (or Union[str, None])

(but after the second if it's str, because of narrowing)

_cache: dict[str, str] (see next section))

As you can see, it's not always straight-forward; but hopefully it matches your issues of what kind of value each variable holds at what point.

What if you want to add two lists of numbers elementwise? You might do this:

def zip_add(list1: list, list2: list) -> list:

if len(list1) != len(list2):

raise ValueError("Expected lists of the same length")

return [a + b for a, b in zip(list1, list2)]This is better than nothing — the type checker will complain if you'll try to zip_add an integer and a string. But it will happily allow you to zip_add a list of integers and a list of strings. There must be a better way!

This is where typing.List comes in — it allows you to say what elements the list must contain.

from typing import List

def zip_add(list1: List[int], list2: List[int]) -> List[int]:

if len(list1) != len(list2):

raise ValueError("Expected lists of the same length")

return [a + b for a, b in zip(list1, list2)]List[int] stands for a list object, in which all elements are int objects. For example: [1, 2, 3], [1 + 2] and [].

Now zip_add([1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6]) will satisfy the type checker, but zip_add(["foo", "bar"], [1, 0]) will not.

dict has a similar typing counterpart — Dict. It's different in that it's parametrized by two types, not one: the key type and the value type:

def print_salaries(employees: Dict[str, int]) -> None:

for name, salary in employee.items():

print(f"{name} has salary of ${salary}")The type hint says that print_salaries accepts a dictionary where all keys are strings, and all values are integers. An example would be {"alice": 420, "bob": 420}.

A similar pattern applies to Set, Frozenset, Deque, OrderedDict, DefaultDict, Counter, ChainMap:

from typing import Set

def extract_bits(numbers: Set[int]) -> Set[int]:

return number & {0, 1}Since Python 3.9, ordinary types like list, dict, tuple, type, set, frozenset, ... allow being subscripted. So our first example would look like this:

def zip_add(list1: list[int], list2: list[int]) -> list[int]:

if len(list1) != len(list2):

raise ValueError("Expected lists of the same length")

return [a + b for a, b in zip(list1, list2)]No import from typing required — just index into the list class!

Tuples are a bit more complicated, because they're used for different purposes:

- a 'heterogenous record' of fixed size (like

('alice', 420)or(1, 2)[meaning a point on a 2D grid]) - an immutable list of values having the same type (like

(1, 2, 3, 4, 5))

Type hints for tuples support both cases.

Let's start with the first usage. We'll need to import typing.Tuple (or, if you're on 3.9 or above, just use tuple), and simply pass the expected types in order (there can be as many as you want.

def print_salary_entry(entry: Tuple[str, int]) -> None:

name, salary = entry

print(f"Salary of {name}: {salary}")This type hint means that print_salary_entry accepts a tuple of length 2 where the first element is a string and the second element is an integer.

You can nest types as deeply as you want. For example, you might have volunteers, not just employees:

def print_salary_entry(entry: Tuple[str, Optional[int]]) -> None:

name, salary = entry

if salary is None:

print(f"{name} is a volunteer")

else:

print(f"Salary of {name}: {salary}")Here the type hint means that the print_salary_entry accepts a tuple of length 2 where the first element is a string and the second element is an integer or None.

Sometimes a tuple is used as an immutable list. For example, you might want to store a sequence of objects and make sure it doesn't change. Another use is in arbitrary arguments (usually spelled as *args). In this case, the tuple value is annotated as Tuple[YourType, ...]. ... is an ellipsis — a very niche object that found its use here. Example:

from typing import Tuple

def sum_numbers(numbers: Tuple[int, ...]) -> int:

total = 0

for number in numbers:

total += number

return totalAs I said before, in Python 3.9 and higher you can simply use tuple instead of typing.Tuple.

The next article in the series is: TypeVars explained

19