18

How We are Making a Video Game in Python #2

Before we begin this is the second in the series which was originally called; The Makings of Pycraft #1.

Pycraft, a 3D open-source open-world video game made in python with Pygame, Numpy and PyOpenGL.

This article, released at the start of every month will document what changes have been made to the project, what challenges we faced and how we overcame them and how and where you can install this project from. For anyone wondering, this is to accompany the Pycraft weekly updates released weekly on Friday on my twitter page (@pycraftdev on twitter: twitter.com/PycraftDev), under the #PycraftTJ. I am Tom Jebbo, the lead developer and graphics designer and I hope you enjoy both playing the game and reading this article!

What is a Computer Program?

What are Loops?

What is Error Handling?

What is Data Validation?

What are Subroutines?

Why am I telling you all this?

It’s time for some updates on Pycraft

Timeline

Final Words

Links and Credits

Any computer program, is an algorithm, which is a set of abstracted (which is a group of broken-down larger instructions) and decomposed (which means the irrelevant information is omitted) set of instructions can be categorised into a few different sections, to start with, its complexity.

The complexity of the algorithm is typically one of two types, its either a really simple program, for example a simple two-or-three-line password checker program, or a complex program, such as a game or other application.

Often a simple program can also be defined as a sequence which, by definition means; ‘a particular order in which related things follow each other.’ — Bing Dictionary. But put into the context of programming, a sequence a program with no looping, that follows instructions in a set order, often taking inputs at the top, processing them in the middle before giving an output at the end, an often referred to example of this is a password checker; like the one pictured below:

Now, larger programs, like my Python project Pycraft, which I’ll get to in a moment will frequently feature loops. These loops will continue to iterate (that is the act of repeating something) until a condition is met, often these loops can take many forms, like Python’s while loops and for-loops. Which can be defined as pre-condition loops because they take a condition and will run only if that condition is met.

Other languages can also feature loops like repeat-until loops which will repeat a section of code before working out if it needs to loop that area of code again. This process of running first and checking later is known as a post-condition loop. In Python we use indentation (that is, inset bits of code) to show which parts of code are in a loop. In Python we also use indentation to determine what sections of code are to occur after an event, some examples of these include the if-elif-else statement, which compares multiple objects and if the result is true, (that is to say is correct), will run the indented syntax, often an if-elif-else statement can look similar to a loop, because they both compare multiple objects to give an output. A good example of this would be to expand upon our simple password checker used in the last example:

In programming an error occurs when the program either encounters something it doesn't understand or that wasn’t expected, there are many different types of error in computing. Let’s start with the syntax error.

These errors cannot be handled by the program in any way as the program doesn't run, it’s an error picked up as the language is compiled. These errors occur when the program is compiling and cause the process to stop, to prevent potential damage to the hardware, in Python a good example of a syntax error is using a semi-colon instead of a colon at the end of a condition.

The next error is a Runtime Error, these are often discovered in the running of a program (hence the name Runtime Errors) and are easy to fix, they can occur when the program attempts to call a variable that doesn’t exist (Name Errors), or when you are attempting to add data of one type to data of another (which is called a Type Error). These are just two examples but there are lots. For example, an array data structure can in no way have the string “Hello World” added to it (It can however be appended through the .append() syntax). These types of error can also occur if data validation is not happening beforehand, you don’t have to do this on every variable, but when users enter data into programs it is often advised you prepare the program for any manner of data the user throws at it, this is called testing, which I’ll go over later.

The final and (ask any developer if you dare) worst type of error is the logic error, these are mentioned here but rarely cause the program to crash, they occur when the wrong check is performed in a condition, which can occur frequently with the number of conditions in a large program, which can make these errors really common and tricky to fix. In addition to this logic errors can go undetected in software indefinitely (until it's encountered upon by some unfortunate user). This is why large programs such as games and applications often have a series of testers that agree to try the program in both typical use cases (like entering numbers into a calculator) and extreme use cases like entering text and symbols into say that example of a calculator, and seeing how the program handles all that. This is called beta-testing and this is just one of multiple checks they can do.

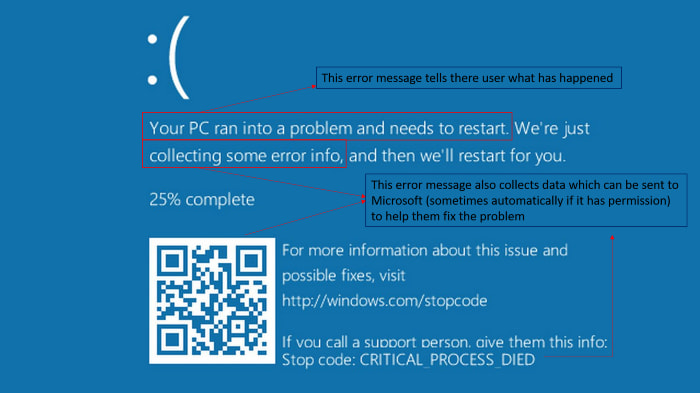

These are just three of the most common errors encountered in programming, even Python has lots more but these are the three main types that appear in most languages. Enter the try-except-else-finally syntax, this handy bit of code allows you to run problematic programs, and if an error does occur, the program doesn't crash, it can handle it appropriately (hence error handling). This syntax is often used when validating user inputs, like making sure they are the right data type, or for use in games or large programs — even Windows has error handling, because of its large amounts of use-cases, developers can’t program for them all so a program will pick the best one, however if that doesn’t work then windows might crash, now in most programs they won't ‘just close’. A good error display will feature a message telling the user what happened, often a code which can be given to a developer to help them fix the issue in an update, and often something that goes on much ore behind the scenes the program will also attempt to save user data and, if it is allowed will try and send error reports back to the developer. In Windows 10, all this is packed into something referred to as ‘The Blue Screen of Death’ or ‘BSoD’. You might notice that these error displays, in any program, should get less and less frequent with every update as errors are fixed that where not picked up in beta testing.

Data validation is a key part of any piece of software which will be interacting with the user through inputs. In a game it’s not necessary to validate a keypress or mouse movement, even though these are technically user inputs still. In this section we are talking about text inputs. If a game or any program asks the user directly for an input, say a game wants a name or a web-browser wants a valid web address, then the data the user enters should be validated. This is because the user might not enter data in the way a program might expect it to be, which leads to errors as seen in the previous chapter on error handling.

We can use errors to help us detect what form the user has entered the data in as, and how the program has accepted it, as well as using other methods involving pre-programmed precautions and checks to mitigate the risk of an error occurring.

Let’s start by talking about the most common reason why data must be validated by a program, and that’s so that the program knows how the data should be compared. In a condition statement in Python, the physical data is checked, like for example:

if “12345” == “12345”:In this case the if-elif-else statement would be true because both of the pieces of data there the same, however an additional check is performed by Python, called a data type check, which is why data validation is so important, if the user where to, say, enter a number -for example- in a calculator program, and that number was automatically stored as a string, and you then tried to add an integer the program would return a type error as the number the user entered was stored as a string and so not able to be added to by an integer.

Data validation consists of a few checks, and a data type check is just one of them, another form of data validation could be the presence check, which really simply checks the data the user has entered to make sure the data is not blank. This is not to be confused with the range check which checks the data the user has entered is in a range of valid lengths, a good example of this is a password checker that might ask: ‘Enter a password between 8 and 16 characters in length’.

The final, more advanced data validation method is the format checker, which makes sure that the data the user has entered is in a valid format. This is often a much more advanced feature that is rarely used, however a good example of this could be typing in a postcode, the postcode might be able to satisfy the other types of data validation, but if the user entered their email in the postcode option this is where that would be flagged up and the user notified of their mistake. RegEx (or Regular Expression) is often used here as it's a very good way to check a data’s format.

You might be, by now questioning why I’ve not given examples of code for each of these features, and the reason why is simply because Python doesn’t provide a direct syntax for each of these validations, instead it is left to the user to decide how they want to implement their data validation methods. However, Python does have the ‘len()’ syntax which can be used to get the length of any given string.

Right, now you have a system for telling the user that their inputs are not in the right format, and you have your system working and programmed, your done with this topic now…right? No. Now you have to go through and test your input and its data validation by entering data that would be classed as acceptable by the program (which means it will, in theory pass the data validation section of your algorithm), Boundary data (Which is data that the program should accept but is on the edge of what the program should accept, like entering an 8-or-16-digit code into a program that accepts data that's between the lengths of 8 and 16 characters), and finally erroneous data (which is why we have these checks, the program should not accept this data and display a suitable message as to why it was not accepted).

To conclude this chapter, we must first make note of a few important points. Number one; data validation checks whether the data is appropriate, not the accuracy of the data, and: Number two; it is good programming practice to never ever, even after validation, directly execute a user input in a program, whether that is using Pythons exec() syntax or by other means, as this can lead to the user entering something that could damage the program, the device or entire network, for more information on this topic check out this article by Data Flair; data-flair.training/blogs/python-exec-function

The last fundamental component of large programs is the subroutine, these are categorised into two sub-sections, procedures and functions. There is one key difference between the two, as they are not the same, and that is that a function must include the return syntax and must return data back to where it was called from, whereas a procedure does not.

In any program a subroutine can be used to improve upon line efficiency, this means that it will reduce the total amount of lines the program will use. A subroutine is a bit of stored code that can be accessed at any time by a process called ‘calling’ (like you might call your dog), it summons the subroutine.

A subroutine is defined by the handily named def syntax. Then you must give your subroutine a name (and ideally something relevant) and reference any parameters it may need in adjacent brackets. Oh! And don't forget that colon at the end to round things off. From there you simply write your code inside that subroutine (with indentation) and every time you need to reference that section of code, you just call its name and parameters. Please note though that the names you may place in the brackets when you make the subroutine are the names of the data which you reference in your subroutine, these don’t have to be continuations of variable names from the main code, although that can be a good indication as to what goes where.

The reason we add brackets and data to a subroutine is because they only have access to the variables defined in them, this is called a local scope. Any variables in Python created with the global syntax, can be accessed from within the subroutine, and variables that are defined in the subroutine with the global syntax can be also accessed by the main program. Local variables are the variables created in the subroutine and are unable to be accessed by the main program. However, you can create a local variable in the main program with Python’s local syntax, so that variable cannot be accessed in a subroutine even though it was made in the main program. The reason this occurs is because the subroutines you defined are stored in a physically different area of RAM when the program is running to the rest of the program, which is why you can access subroutines from imported modules without having to have the whole project loaded.

Having global variables are good, they make programming subroutines and other forms of structures programs (with classes and imports which I’ll discuss in a later article) much easier to program and give variables to. However, when you import that program into another, say to use that subroutine CheckPassword(password) from our example, you might be in for a nasty surprise, all the variables you created in that program with global scope will be imported also, which can lead to variable clashes (where a variable in a program might be an array and its suddenly overwritten to be an integer because you have called a subroutine with global variables, leading to potential errors), logical errors and runtime errors. Using variables with a global scope is up to the developer, but can have unforeseen consequences.

In any program the fundamental concepts I have discussed above and many more are used, often hundreds or thousands of times depending on the size and complexity of the program. But never look at a program, written in any language, and think; “Gosh that's really complicated, I would never be able to do that!” You absolutely can, even with a basic understanding, a program, application or game may look really big and complex, but the bits that make it work, that make all the GUIs, animations, and design are often just these few fundamental features used lots of times in part of a bigger picture.

I have been working on (and worked on) countless numbers of games and applications, and I’m often seeing people put off doing the same because a computer program may at first appear a really complex thing, but even with a basic knowledge of programming you could do anything (although time is a really important thing that you need to bear in mind when attempting a large project). Pycraft has taken over three years of research, design and programming!

On the 19th of September 2021, Pycraft v0.9 was launched, after exactly 70 days of programming and brought an array of exciting and much needed features to Pycraft, and to celebrate the upcoming three-year anniversary of Pycraft, as I have with every year. There will be a small update, Pycraft v0.9.1 that will feature an entire reprogramming of the game, which is at the time of writing about 50% complete already! As well as a few bug fixes and UI improvements. Pycraft will also be updated soon to support the up-and-coming release of Windows 11.

In the near future for Pycraft there will be a series of smaller releases, and each of these releases will add features towards Pycraft v0.10. This is because during those 70 days of programming to the release of v0.9, Pycraft appeared quite quiet to the rest of the world, and releasing sub-updates has the added advantage of getting out previews quicker to the world, which means more beta testing and more bug fixes before the game is compiled in Pycraft v0.10. The compiling process will only happen at these larger releases. Pycraft (.exe) files at current only support 64-bit versions of Windows 10, however support for 32-bit as well as support (and hopefully testing) will take place for Mac, Linux and other Windows based operating systems.

At present this looks to be the schedule for Pycraft updates:

Pycraft v0.9 — Released on the 19th of September 2021!

Pycraft v0.9.1 — Will be released by the 10th of October and will feature a complete programming redesign, as well as some UI improvements.

Pycraft v0.9.2 — Will feature work towards map loading in game and some tweaks to the OpenGL environment, and hopefully fixing that skybox!

At the end of October Pycraft will be 3 years old!

Pycraft v0.9.3 — Will add better lighting, as well as a sun to the game! This update will also include the introduction of day and night cycles (20 minutes from sunset to sunrise), including clouds and dynamic skyboxes (featuring stars and night and day scenes).

Pycraft v0.9.4 — This will add weather events to the sky box, as well as updated sounds, including libraries for night sounds, day sounds, rain sounds, snow sounds, ambient music, footstep sounds on wet ground, footstep sounds on snow, hurt sounds, civilisation sounds, ocean sounds, and environmental sounds (like trees and grass).

Pycraft v0.9.5 — This will add an ocean to the OpenGL environment, as well as hopefully fixed collisions and much improved frame rates in game.

Pycraft v0.9.6 — This update will add structures (like buildings, trees, grass, boats, people) to the game.

Pycraft v0.9.7 — This update will feature interactions with the objects added in the previous update.

Pycraft v0.9.8 — This update will feature the addition of a story line to the game.

Pycraft v0.9.9 — This update will feature a start position in game, as well as saving your progress and loading them on a start screen, this update will also begin the process of playthrough!

Pycraft v0.9.10 — This update will feature a GUI, as well as an in-game character!

Pycraft v0.10 — This update is set to be released in Spring of 2022 at the earliest! This will showcase all the sub-updates to Pycraft v0.9, as well as featuring a compiled version. This update will also improve upon features added in sub-updates, as well as improving performance, and lots of bug fixes.

Pycraft v0.10.1 — This update will feature the addition of inventory items.

Pycraft v0.10.2 — This update will feature improvements to the inventory and map GUIs, this is as far as the plan reaches so far!

Thank you for reading this article, I hope that you have liked this article and hopefully you have learned something about either Python or about the future plans for Pycraft. If you want to share this article that would be greatly appreciated! Pycraft v0.9 took a very long time to develop, and a lot of work was put into both that update, Pycraft as a whole and writing these articles for you, as a result if you have any questions feel free to message me here on twitter (twitter.com/PycraftDev) or drop me an email at (ThomasJebbo@gmail.com).

Normally I’d have gone over highlight features and the “quick bits” about the latest update to Pycraft, however a lot of those features were mentioned in the last article and on my GitHub page. This style of writing however is not gone and as work progresses towards Pycraft v0.10, and all of the sub-updates to Pycraft v0.9, I will be going over some of the new features and explaining how they have been programmed, as well as any problems I faced and how I overcame them (so hopefully you don’t have to!).

I’m regularly on Twitter so feel free to message me with any questions you may have on the project, for feel free to let me know of any typos and mistakes, although every attempt has been made to make these publications as accurate as possible, I am human and do (very occasionally) make mistakes.

Thank you for reading this article, that’s really appreciated. And remember; anyone can learn to code. And games like my own, which I’m still working on, from a programming point of view are possible for everyone!

My Twitter Page: www.twitter.com/PycraftDev

My GitHub page: www.github.com/PycraftDeveloper

Pycraft can be found here: www.github.com/PycraftDeveloper/Pycraft

With thanks to:

Pygame (www.pygame.org), Numpy (www.numpy.org), Pillow (PIL) (www.python-pillow.org), Python (www.python.org), Tkinter, PyAutoGUI (https://github.com/asweigart/pyautogui), psutil (https://github.com/giampaolo/psutil), GitHub (www.github.com), PyOpenGL (PyOpenGL — The Python OpenGL Binding: https://github.com/mcfletch/pyopengl), OpenGL (www.opengl.org), YouTube, Windows, Visual Studio Code (code.visualstudio.com), Microsoft and My amazing Twitter followers and community.

Please note any links are not moderated by me (outside of my Twitter and GitHub pages), they are safe links at the time of writing however I do not control the content on them.

18