19

Memory management using Smart Pointers in C++ - Part 2

In the previous article on Memory management using smart pointers (Part 1), we saw that unique_ptr implements unique ownership - only one smart pointer owns the object at a time. But there might be scenarios where you might need to create multiple pointers of the same object and share them; in that case we should use shared pointer(std::shared_ptr). One such scenario could be - using smart pointers for multithreading; sharing a pointers between threads helps to keep the smart pointer alive within threads when other thread using the same smart pointer goes out of scope (i.e, more than one owner manages the lifetime of the object in memory).

std::shared_ptr is a smart pointer that retains shared ownership of an object through a pointer. The same object may be owned by multiple shared_ptr objects. The object is destroyed and its memory deallocated when either of the following happens:

- the last remaining

shared_ptrowning the object is destroyed. - the last remaining

shared_ptrowning the object is assigned another pointer viaoperator=orreset().

Shared pointers keep something called a reference count; which keeps track of the number of pointers to an object (manager object to be specific). As we create more copies of the pointer and they exit scope, the reference count is incremented and decremented accordingly. Finally, when the reference count reaches zero, the underlying memory is freed.

int main()

{

std::shared_ptr<int> sp1 = std::make_shared<int>(2);

std::cout << sp1.use_count() << '\n'; // prints 1

{

std::shared_ptr<int> sp2 = sp1; // object copy -> reference count increments to 2

std::cout << sp1.use_count() << '\n'; // prints 2

} // sp2 goes out of scope hence reference count decrements to 1

std::cout << sp1.use_count() << '\n'; // prints 1

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

} // reference count reaches zero as sp1 goes out of scope; hence object resource is destroyedWhen the managed object is dynamically allocated using shared_ptr, the first shared_ptr object (lets call it sp1) contains two raw pointers, one pointing to the managed object (returned by get()) and another raw pointer pointing to the control block (also called as manager object). The control block contains a pointer to the managed object, two reference counts (the number of shared_ptrs pointing to the manager object and the number of weak_ptrs pointing to the manager object) and depending on how a shared_ptr is initialized, it can also contain other data, such as a deleter and an allocator.

The shared_ptr constructor creates a manager object (dynamically allocated) and the overloaded member functions like shared_ptr::operator-> access the pointer in the manager object to get the actual pointer to the managed object. If another shared_ptr (sp2) is created by copy or assignment from sp1, then it also points to the same manager object, and the copy constructor or assignment operator increments the shared count to show that 2 shared_ptrs are now pointing to the managed object.

Similarly, when weak pointer is created by copy or assignment from the shared_ptr object or another weak_ptr object, it points to the same manager object and the weak pointer count is incremented. When sp1 and the manager object are first created, the shared count will be 1, and the weak count will be 0

The manager object (or control block) contains pointer to the managed object, which is basically used for deleting the object. One interesting fact is that the managed pointer in the manager object may be of a different type (and even have a different value) than the raw pointer in the shared_ptr; that's because shared_ptr stores type-erased deleter in the manager object.

// A shared_ptr<void> managing double

// The raw pointer is void*

// Managed pointer in the manager object is double*

auto sp = std::shared_ptr<void>(new double()); //OKThis leads to an interesting use case where we can avoid incomplete deletion of derived object when derived object pointer is assigned to a base class pointer (of course without virtual destructor). Lets look at an example for incomplete deletion of an object.

struct Base

{

~Base()

{

std::cout << "Base::~Base()\n";

}

};

struct Derived: public Base

{

~Derived()

{

std::cout << "Derived::~Derived()\n";

}

};

int main()

{

Base* base = new Derived;

delete base; // prints Base::~Base(), hence Derived class object is partially destructed

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}Of course the fix for the issue is doing the binding at run time polymorphically (dynamic binding) i.e, using virtual destructor in the base class, which prints

Derived::~Derived()

Base::~Base()If we use shared_ptr we may not need virtual destructor since the smart pointer will take care of it for us. Changing the above code with shared_ptr

struct Base

{

~Base()

{

std::cout << "Base::~Base()\n";

}

};

struct Derived: public Base

{

~Derived()

{

std::cout << "Derived::~Derived()\n";

}

};

int main()

{

std::shared_ptr<Base> base(new Derived);

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

/*

prints

Derived::~Derived()

Base::~Base()

*/In the above code, despite the destructor not being virtual, the correct derived class (Derived) destructor is invoked when the base class (Base) shared_ptr goes out of scope or reset. This works because the manager object (control block) is destroying the object through Derived* deleter and not through the raw pointer Base*. However, the destructor should be declared virtual in the base class to make it operate polymorphically; the above example is just to show how shared_ptr works.

NOTE:

unique_ptr<Base> base(new Derived)do not provide this feature because withunique_ptrdeleter function is part of the type and there is no concept of control block or manager object.

To use shared_ptrlike a raw pointer the arrow operator(->) and dereferencing (*) operator are overloaded.

sp->myMethod();

(*sp)->myMethod();You can call a reset() member function, which will decrement the reference count and delete the pointed-to object if appropriate, and result in an empty shared_ptr that is just like a default-constructed one. You can also reset a shared_ptr by assigning it the value nullptr.

sp.reset();

sp = nullptr;Below is a code sketch to illustrate the basic usage

class MyClass

{

public:

void classMethod();

};

ostream &operator<<(ostream &, const MyClass &);

// ...

// a function can return a shared_ptr

std::shared_ptr<MyClass> find_some_thing();

// a function can take a shared_ptr parameter by value;

std::shared_ptr<MyClass> do_something_with(std::shared_ptr<MyClass> p);

void foo()

{

// the new is in the shared_ptr constructor expression:

std::shared_ptr<MyClass> sp1(new MyClass);

// ...

std::shared_ptr<MyClass> sp2 = sp1; // sp1 and sp2 now share ownership of the MyClass

// ...

std::shared_ptr<MyClass> p3(new MyClass); // another MyClass

sp1 = find_some_thing(); // sp1 may no longer point to first MyClass

do_something_with(sp2);

sp3->classMethod(); // call a member function like built-in pointer

cout << *sp2 << endl; // dereference like built-in pointer

// reset with a member function or assignment to nullptr:

sp1.reset(); // decrement count, delete if last

sp2 = nullptr; // convert nullptr to an empty shared_ptr, and decrement count;

}

// sp1, sp2, sp3 go out of scope, decrementing count, delete the MyClass if lastHaving two classes one that inherits from another, when trying to assign a smart pointer variable of the derived class to a smart pointer variable of the base class it is required to use std::static_pointer_cast in place of the normal static_cast (used with raw pointers). It will be useful to remove the suggestion to use the static_cast and include the suggestion to use the std::static_pointer_cast.

For example:

#include <memory>

#include <iostream>

class Base{

public:

Base(){std::cout << "Base::Base()" << std::endl;}

~Base(){std::cout << "Base::~Base()" << std::endl;}

void print(){std::cout << "Base::print()" << std::endl;}

};

class Derived:public Base{

public:

Derived(){std::cout << "Derived::Derived()" << std::endl;}

~Derived(){std::cout << "Derived::~Derived()" << std::endl;}

void print(){std::cout << "Derived::print()" << std::endl;}

};

int main()

{

std::shared_ptr<Base> b_ptr = std::make_shared<Derived>();

b_ptr->print();

auto d_ptr = std::static_pointer_cast<Derived>(b_ptr);

d_ptr->print();

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

/* OUTPUT

Base::Base()

Derived::Derived()

Base::print()

Derived::print()

Derived::~Derived()

Base::~Base()

*/When we create an object with new operator in shared_ptr there will be two dynamic memory allocations that happen, one for object from the new and the second is the manager object created by the shared_ptr constructor. Since memory allocations are slow, creating shared_ptr is slow when compared to raw pointer. To solve this problem C++11 has introduced the function template make_shared that does a single memory allocation big enough to hold both manager object and the new object, with the constructor parameters passed, which returns a shared_ptr of required type.

std::shared_ptr<MyClass> sp(new MyClass("some string")) // Bad practice - two allocations

std::shared_ptr<MyClass> sp(std::make_shared<MyClass>("some string")); // Good practice - one allocationUsing make_shared also avoids explicit use of new, promoted in the slogan "no naked new!". Because only a single memory allocation is involved when you use make_shared to initialize a shared_ptr, you can expect improved performance over the separate allocation approach.

In the situation where the class member function needs to pass a pointer to this object to another function that accepts the shared_ptr to that class object as argument then we can use std::enable_shared_from_this to create an object that returns shared_ptr from this. Hence the class of the objects has to be derived from std::enable_shared_from_this, which unlocks the special method shared_from_this, which can be used to create shared_ptr from this.

#include <iostream>

#include <memory>

class MyClass;

void someFunction(std::shared_ptr<MyClass> shareMe)

{

std::cout << "someFunction: shareMe.use_count(): " << shareMe.use_count() << std::endl;

}

class MyClass : public std::enable_shared_from_this<MyClass>

{

public:

std::shared_ptr<MyClass> getShared()

{

return shared_from_this();

}

void classMethod()

{

//....

someFunction(getShared());

//....

}

};

int main()

{

std::cout << std::endl;

std::shared_ptr<MyClass> shareMe(new MyClass);

std::shared_ptr<MyClass> shareMe1 = shareMe->getShared();

{

auto shareMe2(shareMe1);

std::cout << "main(): shareMe.use_count(): " << shareMe.use_count() << std::endl;

}

std::cout << "main(): shareMe.use_count(): " << shareMe.use_count() << std::endl;

shareMe1.reset();

std::cout << "main(): shareMe.use_count(): " << shareMe.use_count() << std::endl;

shareMe->classMethod();

std::cout << std::endl;

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}From performance perspective taking shared_ptr by copy or by reference make significant difference.

//

void functionbyReference(std::shared_ptr<int> &refPtr) // Not a good practice

{

std::cout << "refPtr.use_count(): " << refPtr.use_count() << std::endl;// prints 1

}

void functionbyCopy(std::shared_ptr<int> cpyPtr)

{

std::cout << "cpyPtr.use_count(): " << cpyPtr.use_count() << std::endl; // prints 2

}

int main()

{

auto sp(std::make_shared<int>(2021));

std::cout << "sp.use_count(): " << sp.use_count() << std::endl; // prints 1

functionbyReference(sp);

functionbyCopy(sp);

std::cout << "sp.use_count(): " << sp.use_count() << std::endl; // prints 1

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}The reference count is incremented a when function takes shared_ptr by copy; since incrementing and decrementing the reference count is an expensive operation and hence results in a performance difference. The quick benchmark test states the measurable difference in performance (almost twice).

NOTE: The best practice in C++ is always to have clearly defined ownership semantics for your objects. The pass by reference of the smart pointer defy this rule; Hence, copy the shared pointer when a new function or object needs to share ownership of the pointee.

The problem with shared_ptr is that if there is a ring, or cycle of an objects that have shared_ptr to each other, they keep each other alive - they won't get deleted as they are holding each other (i.e, still has a shared_ptr pointing to them) leading to memory leak.

//Forward declaration

struct MyClass2;

struct MyClass3;

struct MyClass1 {

std::shared_ptr<MyClass3> sp3;

};

struct MyClass2 {

std::shared_ptr<MyClass1> sp1;

};

struct MyClass3 {

std::shared_ptr<MyClass2> sp2;

};

Lets look at an example that causes cyclic reference problem

#include <memory>

#include <iostream>

struct MyClassB;

struct MyClassA

{

std::shared_ptr<MyClassB> b;

~MyClassA() { std::cout << "MyClassA::~MyClassA()\n"; }

};

struct MyClassB

{

std::shared_ptr<MyClassA> a;

~MyClassB() { std::cout << "MyClassB::~MyClassB()\n"; }

};

void useClassAnClassB()

{

auto a = std::make_shared<MyClassA>();

auto b = std::make_shared<MyClassB>();

a->b = b;

b->a = a;

}

int main()

{

useClassAnClassB();

std::cout << "Finished using A and B\n";

}

/*OUTPUT

Finished using A and B

*/If both references are shared_ptr then that says MyClassA has ownership of MyClassB and MyClassB has ownership of MyClassA, which should ring alarm bells. In other words, MyClassA keeps MyClassB alive and MyClassB keeps MyClassA alive.

In this example the instances a and b are only used in the useClassAnClassB() function so we would like them to be destroyed when the function ends but as we can see when we run the program the destructors are not called.

The memory leak summary is as shown below.

==1969133==

==1969133== LEAK SUMMARY:

==1969133== definitely lost: 32 bytes in 1 blocks

==1969133== indirectly lost: 32 bytes in 1 blocks

==1969133== possibly lost: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==1969133== still reachable: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==1969133== suppressed: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==1969133==

==1969133== For lists of detected and suppressed errors, rerun with: -s

==1969133== ERROR SUMMARY: 1 errors from 1 contexts (suppressed: 0 from 0)C++11 includes a solution: weak smart pointers: these only observe an object but do not influence its lifetime.

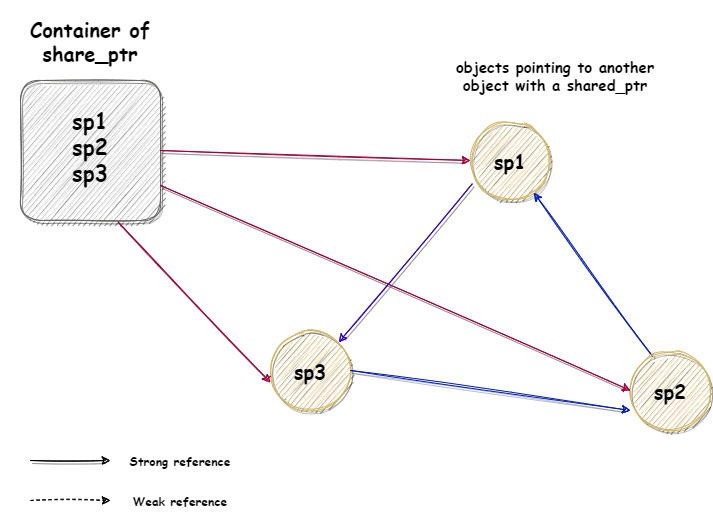

A ring of objects can point to each other with weak_ptrs, which point to the managed object but do not keep it in existence. This is shown in the diagram below, where the "observing" relations are shown by the dotted arrows.

If the shared pointer container is emptied, the three objects in the ring are automatically deleted because no other shared pointers point to them; weak pointers, like raw pointers, do not keep the pointed-to object "alive" and hence cycle problem has been resolved.

Solution to the problem

The solution to the cyclic reference problem example is to decide who owns who. Lets say MyClassA owns MyClassB but MyClassB does not own MyClassA then we replace the reference to MyClassA in MyClassB with a weak_ptr like

#include <memory>

#include <iostream>

struct MyClassB;

struct MyClassA

{

std::shared_ptr<MyClassB> b;

~MyClassA() { std::cout << "MyClassA::~MyClassA()\n"; }

};

struct MyClassB

{

std::weak_ptr<MyClassA> a;

~MyClassB() { std::cout << "MyClassB::~MyClassB()\n"; }

};

void useMyClassAnMyClassB()

{

auto a = std::make_shared<MyClassA>();

auto b = std::make_shared<MyClassB>();

a->b = b;

b->a = a;

}

int main()

{

useMyClassAnMyClassB();

std::cout << "Finished using A and B\n";

}

/*OUTPUT

MyClassA::~MyClassA()

MyClassB::~MyClassB()

Finished using A and B

*/Then if we run the program we see that a and b are destroyed as we expect. And memory leak summary (for the above code) below shows that, no memory is leaked and the objects are destroyed gracefully.

==1969207== HEAP SUMMARY:

==1969207== in use at exit: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==1969207== total heap usage: 4 allocs, 4 frees, 73,792 bytes allocated

==1969207==

==1969207== All heap blocks were freed -- no leaks are possible

==1969207==

==1969207== For lists of detected and suppressed errors, rerun with: -s

==1969207== ERROR SUMMARY: 0 errors from 0 contexts (suppressed: 0 from 0)The definition of weak_ptr is designed to make it relatively foolproof, so as a result there is very little you can do directly with a weak_ptr. For instance, you can't dereference it; neither operator* nor operator-> is defined for a weak_ptr, you can not get pointer to an object - there is no get() function.

During initialization, the weak_ptr is constructed as empty; the weak_ptr object can only be initialized by copy or assignment from the shared_ptr or an existing weak_ptr to the object.

std::shared_ptr<MyClass> sp(new Thing);

std::weak_ptr<MyClass> wp1(sp); // construct wp1 from a shared_ptr

std::weak_ptr<MyClass> wp2; // an empty weak_ptr - points to nothing

wp2 = sp; // wp2 now points to the new MyClass

std::weak_ptr<MyClass> wp3 (wp2); // construct wp3 from a weak_ptr

std::weak_ptr<MyClass> wp4

wp4 = wp2; // wp4 now points to the new MyClass.You can not refer to an object directly using weak_ptr; you have to get a shared_ptr from it with lock() member function.

std::shared_ptr<MyClass> sp2 = wp2.lock(); // get shared_ptr from weak_ptrThe lock() function checks the state of the manager object to see if the managed object still exists. if it does not exist, returns an empty shared_ptr and if managed object exists, it returns a shared_ptr to the manager object.

std::shared_ptr<MyClass> sp = wp.lock(); // get shared_ptr from weak_ptr

if(sp)

sp->do_something(); // tell the MyClass to do something

else

std::cout << "The MyClass is gone!\n";ask the weak_ptr if it has expired

bool is_sharedptr_alive(std::weak_ptr<MyClass> wp)

{

if(wp.expired())

{

std::cout << "The MyClass is gone!\n";

return false;

}

return true;

}The weak_ptr can tell looking at the manager Object whether the managed object is still there; if the pointer and/or shared count are zero, the managed object is gone, and no attempt should be made to refer to it. If the pointer and shared count are non-zero, then the managed object is still present, and weak_ptr can make the pointer to it available.

C++11 shared_ptr and weak_ptr work well enough to automate or simplify your memory management. std::weak_ptr is a smart pointer that holds weak reference to an object that is managed by std::shared_ptr. The main intension of using std::weak_ptr is used to break circular references of std::shared_ptr.

19