26

Build a Plagiarism Checker Using Machine Learning

Plagiarism is rampant on the internet and in the classroom. With so much content out there, it’s sometimes hard to know when something has been plagiarized. Authors writing blog posts may want to check if someone has stolen their work and posted it elsewhere. Teachers may want to check students’ papers against other scholarly articles for copied work. News outlets may want to check if a content farm has stolen their news articles and claimed the content as its own.

So, how do we guard against plagiarism? Wouldn’t it be nice if we could have software do the heavy lifting for us? Using machine learning, we can build our own plagiarism checker that searches a vast database for stolen content. In this article, we’ll do exactly that.

We’ll build a Python Flask app that uses Pinecone — a similarity search service — to find possibly plagiarized content.

Let’s take a look at the demo app we’ll be building today. Below, you can see a brief animation of the app in action.

The UI features a simple textarea input in which the user can paste the text from an article. When the user clicks the Submit button, this input is used to query a database of articles. Results and their match scores are then displayed to the user. To help reduce the amount of noise, the app also includes a slider input in which the user can specify a similarity threshold to only show extremely strong matches.

As you can see, when original content is used as the search input, the match scores for possibly plagiarized articles are relatively low. However, if we were to copy and paste the text from one of the articles in our database, the results for the plagiarized article come back with a 99.99% match!

So, how did we do it?

In building the app, we start with a dataset of news articles from Kaggle. This dataset contains 143,000 news articles from 15 major publications, but we’re just using the first 20,000. (The full dataset that this one is derived from contains over two million articles!)

Next, we clean up the dataset by renaming a couple columns and dropping a few unnecessary ones. Then, we run the articles through an embedding model to create vector embeddings — that’s metadata for machine learning algorithms to determine similarities between various inputs. We use the Average Word Embeddings Model. Finally, we insert these vector embeddings into a vector database managed by Pinecone.

With the vector embeddings added to the database and indexed, we’re ready to start finding similar content. When users submit their article text as input, a request is made to an API endpoint that uses Pinecone’s SDK to query the index of vector embeddings. The endpoint returns 10 similar articles that were possibly plagiarized and displays them in the app’s UI. That’s it! Simple enough, right?

If you’d like to try it out for yourself, you can find the code for this app on GitHub. The README contains instructions for how to run the app locally on your own machine.

We’ve gone through the inner workings of the app, but how did we actually build it? As noted earlier, this is a Python Flask app that utilizes the Pinecone SDK. The HTML uses a template file, and the rest of the frontend is built using static CSS and JS assets. To keep things simple, all of the backend code is found in the app.py file, which we’ve reproduced in full below:

This file contains hidden or bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| from dotenv import load_dotenv | |

| from flask import Flask | |

| from flask import render_template | |

| from flask import request | |

| from flask import url_for | |

| import json | |

| import os | |

| import pandas as pd | |

| import pinecone | |

| import re | |

| import requests | |

| from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer | |

| from statistics import mean | |

| import swifter | |

| app = Flask(__name__) | |

| PINECONE_INDEX_NAME = "plagiarism-checker" | |

| DATA_FILE = "articles.csv" | |

| NROWS = 20000 | |

| def initialize_pinecone(): | |

| load_dotenv() | |

| PINECONE_API_KEY = os.environ["PINECONE_API_KEY"] | |

| pinecone.init(api_key=PINECONE_API_KEY) | |

| def delete_existing_pinecone_index(): | |

| if PINECONE_INDEX_NAME in pinecone.list_indexes(): | |

| pinecone.delete_index(PINECONE_INDEX_NAME) | |

| def create_pinecone_index(): | |

| pinecone.create_index(name=PINECONE_INDEX_NAME, metric="cosine", shards=1) | |

| pinecone_index = pinecone.Index(name=PINECONE_INDEX_NAME) | |

| return pinecone_index | |

| def create_model(): | |

| model = SentenceTransformer('average_word_embeddings_komninos') | |

| return model | |

| def prepare_data(data): | |

| # rename id column and remove unnecessary columns | |

| data.rename(columns={"Unnamed: 0": "article_id"}, inplace = True) | |

| data.drop(columns=['date'], inplace = True) | |

| # combine the article title and content into a single field | |

| data['content'] = data['content'].fillna('') | |

| data['content'] = data.content.swifter.apply(lambda x: ' '.join(re.split(r'(?<=[.:;])\s', x))) | |

| data['title_and_content'] = data['title'] + ' ' + data['content'] | |

| # create a vector embedding based on title and article content | |

| encoded_articles = model.encode(data['title_and_content'], show_progress_bar=True) | |

| data['article_vector'] = pd.Series(encoded_articles.tolist()) | |

| return data | |

| def upload_items(data): | |

| items_to_upload = [(row.id, row.article_vector) for i, row in data.iterrows()] | |

| pinecone_index.upsert(items=items_to_upload) | |

| def process_file(filename): | |

| data = pd.read_csv(filename, nrows=NROWS) | |

| data = prepare_data(data) | |

| upload_items(data) | |

| pinecone_index.info() | |

| return data | |

| def map_titles(data): | |

| return dict(zip(uploaded_data.id, uploaded_data.title)) | |

| def map_publications(data): | |

| return dict(zip(uploaded_data.id, uploaded_data.publication)) | |

| def query_pinecone(originalContent): | |

| query_content = str(originalContent) | |

| query_vectors = [model.encode(query_content)] | |

| query_results = pinecone_index.query(queries=query_vectors, top_k=10) | |

| res = query_results[0] | |

| results_list = [] | |

| for idx, _id in enumerate(res.ids): | |

| results_list.append({ | |

| "id": _id, | |

| "title": titles_mapped[int(_id)], | |

| "publication": publications_mapped[int(_id)], | |

| "score": res.scores[idx], | |

| }) | |

| return json.dumps(results_list) | |

| initialize_pinecone() | |

| delete_existing_pinecone_index() | |

| pinecone_index = create_pinecone_index() | |

| model = create_model() | |

| uploaded_data = process_file(filename=DATA_FILE) | |

| titles_mapped = map_titles(uploaded_data) | |

| publications_mapped = map_publications(uploaded_data) | |

| @app.route("/") | |

| def index(): | |

| return render_template("index.html") | |

| @app.route("/api/search", methods=["POST", "GET"]) | |

| def search(): | |

| if request.method == "POST": | |

| return query_pinecone(request.form.get("originalContent", "")) | |

| if request.method == "GET": | |

| return query_pinecone(request.args.get("originalContent", "")) | |

| return "Only GET and POST methods are allowed for this endpoint" |

Let’s go over the important parts of the app.py file so that we understand it.

On lines 1–14, we import our app’s dependencies. Our app relies on the following:

-

dotenvfor reading environment variables from the.envfile -

flaskfor the web application setup -

jsonfor working with JSON -

osalso for getting environment variables -

pandasfor working with the dataset -

pineconefor working with the Pinecone SDK -

refor working with regular expressions (RegEx) -

requestsfor making API requests to download our dataset -

statisticsfor some handy stats methods -

sentence_transformersfor our embedding model -

swifterfor working with the pandas dataframe

On line 16, we provide some boilerplate code to tell Flask the name of our app.

On lines 18–20, we define some constants that will be used in the app. These include the name of our Pinecone index, the file name of the dataset, and the number of rows to read from the CSV file.

On lines 22–25, our initialize_pinecone method gets our API key from the .env file and uses it to initialize Pinecone.

On lines 27–29, our delete_existing_pinecone_index method searches our Pinecone instance for indexes with the same name as the one we’re using (“plagiarism-checker”). If an existing index is found, we delete it.

On lines 31–35, our create_pinecone_index method creates a new index using the name we chose (“plagiarism-checker”), the “cosine” proximity metric, and only one shard.

On lines 37–40, our create_model method uses the sentence_transformers library to work with the Average Word Embeddings Model. We’ll encode our vector embeddings using this model later.

On lines 62–68, our process_file method reads the CSV file and then calls the prepare_data and upload_items methods on it. Those two methods are described next.

On lines 42–56, our prepare_data method adjusts the dataset by renaming the first “id” column and dropping the “date” column. It then combines the article title with the article content into a single field. We’ll use this combined field when creating the vector embeddings.

On lines 58–60, our upload_items method creates a vector embedding for each article by encoding it using our model. Then, we insert the vector embeddings into the Pinecone index.

On lines 70–74, our map_titles and map_publications methods create some dictionaries of the titles and publication names to make it easier to find articles by their IDs later.

Each of the methods we’ve described so far is called on lines 95–101 when the backend app is started. This work prepares us for the final step of actually querying the Pinecone index based on user input.

On lines 103–113, we define two routes for our app: one for the home page and one for the API endpoint. The home page serves up the index.html template file along with the JS and CSS assets, and the API endpoint provides the search functionality for querying the Pinecone index.

Finally, on lines 76–93, our query_pinecone method takes the user’s article content input, converts it into a vector embedding, and then queries the Pinecone index to find similar articles. This method is called when the /api/search endpoint is hit, which occurs any time the user submits a new search query.

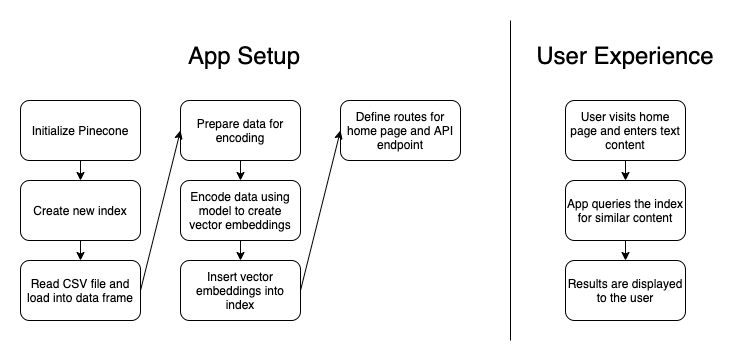

For the visual learners out there, here’s a diagram outlining how the app works:

So, putting this all together, what does the user experience look like? Let’s look at three scenarios: original content, an exact copy of plagiarized content, and “patch written” content.

When original content is submitted, the app responds with some possibly related articles, but the match scores are quite low. This is a good sign, as the content is not plagiarized, so we would expect low match scores.

When an exact copy of plagiarized content is submitted, the app responds with a nearly perfect match score for a single article. That’s because the content is identical. Nice find, plagiarism checker!

Now, for the third scenario, we should define what we mean by “patch written” content. Patch writing is a form of plagiarism in which someone copies and pastes stolen content but then attempts to mask the fact that they’ve plagiarized the work by changing some of the words here and there. If a sentence from the original article says, “He was overjoyed to find his lost dog,” someone might patch write the content to instead say, “He was happy to retrieve his missing dog.” This is somewhat different from paraphrasing because the main sentence structure of the content often stays the same throughout the entire plagiarized article.

Here’s the fun part: Our plagiarism checker does really well in identifying “patch written” content too! If you were to copy and paste one of the articles in the database and then change some words here and there, and maybe even delete a few sentences or paragraphs, the match score will still come back as a nearly perfect match! When I attempted this with a copied and pasted article that had a 99.99% match score, the “patch written” content still returned a 99.88% match score after my revisions!

Not too shabby! Our plagiarism checker looks like it’s working well.

We’ve now created a simple Python app to solve a real-world problem. Imitation may be the highest form of flattery, but no one likes having their work stolen. In a growing world of content, a plagiarism checker like this would be highly useful to authors and teachers alike.

This demo app does have some limitations, as it is just a demo after all. The database of articles loaded into our index only contains 20,000 articles from 15 major news publications. However, there are millions or even billions of articles and blog posts out there. A plagiarism checker like this is only useful if it is checking your input against all the places where your work may have been plagiarized. This app would be better if our index had more articles in it and if we were continuously adding to it.

Regardless, at this point we’ve demonstrated a solid proof of concept. Pinecone, as a managed similarity search service, did the heavy lifting for us when it came to the machine learning aspect. With it, we were able to build a useful application that utilizes natural language processing and semantic search fairly easily, and now we have peace of mind knowing our work isn’t being plagiarized.

26