20

Functional "Control Flow" - Writing Programs without Loops

In my previous post on key principles of functional programming, I explained how the functional programming paradigm differs from imperative programming, and discussed how the the concepts of idempotency and avoidance of side effects are linked to the property of referential transparency that enables equational reasoning in functional programming.

Before we dive into some of the features of functional programming, let’s start with a personal anecdote during my first 3 months of writing Scala code.

I was writing a pure Scala function for a custom Spark UDF which computes revenue adjustments based on a custom tiered adjustment expressed in JSON string. While attempting to express the business logic in pure functional code (since that is the team’s coding style), I got pretty frustrated with my perceived drop in productivity to the point whereby I introduced “if-else” logic into my code in a bid to “get the job done”.

Let’s just say that I learnt a pretty tough lesson during code review for that particular merge request.

“No if-else in functional code, this is not imperative programming… No ifs, no elses. ”

Without “if-else”, how do we write “control flow” in functional programming?

The short answer: function composition.

The long answer: A combination of function composition and functional data structures.

As a deep-dive on each functional design pattern can be pretty lengthy, the focus of this post is to provide an overview of function composition and how it enables a more intuitive approach to designing data pipelines.

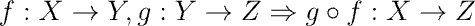

In mathematics, function composition is an operation that takes two functions f and g in sequence and forms a composite function h such that h(x) = g(f(x)) - function g is applied to the result of applying the function f to a generic input x. Mathematically, this operation can be expressed as:

Intuitively, the composite function maps x in X to g(f(x)) in domain Z for all values in domain X.

A useful analogy to illustrate the concept of function composition is making butter toast in an oven with a slice of bread and cold butter. There are two possible operations:

- Toasting in the oven (operation f)

- Spreading butter over the widest surface (operation g)

If we toast the bread in the oven first and spread cold butter over the widest surface of what comes out of the oven, we get a slice of toasted bread with cold butter spread.

If we spread cold butter over the widest surface of the bread first and toast the bread with cold butter spread in the oven, we get a slice of toasted bread with warm butter spread.

And we know that “cold butter spread” != “warm butter spread”

From these examples, we can intuitively infer that the order of function application matters in function composition.

Similarly in designing data pipelines, we often write data transformations by applying functions to results of other functions. The ability to compose functions encourages refactoring of repeated code segments into functions for maintainability and reusability.

The core idea in functional programming is: functions are values.

This feature implies that a function can be [2,3]:

- assigned to a variable

- passed as a parameter to other functions

- returned as a value from other functions

For this to work, functions must be first-class objects (and stored in data structures) in the runtime environment - just like numbers, strings and arrays. First-class functions are supported in all functional languages including Scala, as well as some interpreted languages such as Python.

A key implication resulting from the concept of functions as first-class objects is that function composition can be naturally expressed as a higher-order function.

A higher-order function has at least one of the following properties:

- Accepts functions as parameters

- Returns a function as a value

An example of a higher-order function is map.

When we look at the documentation for the Python built-in function map, it is stated that the map function takes in another function and an iterable as input parameters and returns an iterator that yields the results [4].

In Scala, each of the collection classes in package scala.collections and its subsets contain the map method that is defined by the following function signatures on ScalaDoc [5]:

def map[B](f: (A) => B): Iterable[B] // for collection classes

def map[B](f: (A) => B): Iterator[B] // for iterators that access elements of a collectionWhat the function signatures mean is that map takes a function input parameter f, and f transforms a generic input of type A to a resulting value of type B.

To square each value in a collection of integers, the iterative approach is to traverse each element in the collection, square the element and append the result to a collection of results that expands in length with each iteration.

- In Python:

def square(x):

return x * x

def main(args):

collection = [1,2,3,4,5]

# initialize list to hold results

squared_collection = []

# loop till the end of the collection

for num in collection:

# square the current number

squared = square(num)

# add the result to list

squared_collection.append(squared)

print(squared_collection)In the iterative approach, two state changes occur at each iteration within the loop:

- The

squaredvariable holding the result returned from thesquarefunction; and - The collection holding the results of the square function.

To perform the same operation using a functional approach (i.e. without using mutable variables), the map function can be used to “map” each element in the collection to a new collection with the same number of elements as the input collection - by applying the square operation to each element and collecting the results into the new collection.

- In Python:

def square(x):

return x * x

def main(args):

collection = [1,2,3,4,5]

squared = list(map(square, collection))

print(squared)- In Scala:

object MapSquare {

def square(x: Int): Int = {

x * x

}

def main(args: Array[String]) {

val collection = List[1,2,3,4,5]

val squared = collection.map(square)

println(squared)

}

}In both implementations, the map function accepts an input function that is applied to each element in a collection of values and returns a new collection containing the results. As map has the property of accepting another function as a parameter, it is a higher-order function.

A few quick side-notes on differences between Python and Scala implementations:

- Python

mapvs Scalamap: An iterable function such aslistis needed to convert the iterator returned from the Pythonmapfunction into an iterable. In Scala, there is no need for explicit conversion of the result from themapfunction to an iterable, as all methods in theIterabletrait are defined in terms of an abstract method,iterator, which returns an instance of theIteratortrait that yields the collection’s elements one by one [6]. - How values are returned from a function: While the

returnkeyword is used in Python to return a function result, thereturnkeyword is rarely used in Scala. Instead, the last line within a function declaration is evaluated and the resultant value is returned when defining a function in Scala. In fact, using thereturnkeyword in Scala is not good practice for functional programming as it abandons the current computation and is not referentially transparent [7-8].

When using higher-order functions, it is often convenient to be able to call input function parameters with function literals or anonymous functions without having to define them as named function objects before they can be used within the higher-order function.

In Python, anonymous functions are also known as lambda expressions due to their roots in lambda calculus. An anonymous function is created with the lambda keyword and wraps a single expression without using def or return keywords. For example, the square function in the previous example in Python can be expressed as an anonymous function in the map function, where the lambda expression lambda x: x * x is used as a function input parameter to map:

def main(args):

collection = [1,2,3,4,5]

squared = map(lambda x: x * x, collection)

print(squared)In Scala, an anonymous function is defined in-line with the => notation - where the function arguments are defined to the left of the => arrow and the function expression is defined to the right of the => arrow. For example, the square function in the previous example in Scala can be expressed as an anonymous function with the (x: Int) => x * x syntax and used as a function input parameter to map:

object MapSquareAnonymous {

def main(args: Array[String]) {

val collection = List[1,2,3,4,5]

val squared = collection.map((x: Int) => x * x)

println(squared)

}

}A key benefit of using anonymous functions in higher-order functions is that single-use single-expression functions need not be wrapped explicitly within a named function definition, hence optimizing lines of code and improving code maintainability.

Recursion is a form of self-referential function composition - a recursive function takes the results of (smaller instances of) itself and uses them as inputs to another instance of itself. To prevent an infinite loop of recursive calls, a base case is required as a terminating condition to return a result without using recursion.

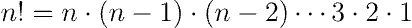

A classic example of recursion is the factorial function, which is defined as the product of all positive integers less than or equal to an integer n:

There are two possible iterative approaches to implementing a factorial function: using for loop, and using while loop.

- In Python:

def factorial_for(n):

# initialize variable to hold factorial

fact = 1

# loop from n to 1 in decrements of 1

for num in range(n, 1, -1):

# multiply current number with the current product

fact = fact * num

return fact

def factorial_while(n):

# initialize variable to hold factorial

fact = 1

# loop till n reaches 1

while n >= 1:

# multiply current number with the current product

fact = fact * n

# subtract the number by 1

n = n - 1

return factIn both iterative implementations of the factorial function, two state changes occur at each iteration within the loop:

- The factorial variable storing the current product; and

- The number being multiplied.

To implement the factorial function using a functional approach , recursion is useful in dividing the problem into subproblems of the same type - in this case, the product of n and (n-1)!).

The basic recursive approach for the factorial function looks like this:

- In Python:

def factorial(n):

# base case to return value

if n <= 0: return 1

# recursive function call with another set of inputs

return n * factorial(n-1)- In Scala:

def factorial(n: Int): Long = {

if (n <= 0) 1 else n * factorial(n-1)

}For the basic recursive approach, the factorial of 5 is evaluated in the following manner:

factorial(5)

if (5 <= 0) 1 else 5 * factorial(5 - 1)

5 * factorial(4) // factorial(5) is added to call stack

5 * (4 * factorial(3)) // factorial(4) is added to call stack

5 * (4 * (3 * factorial(2))) // factorial(3) is added to call stack

5 * (4 * (3 * (2 * factorial(1)))) // factorial(2) is added to call stack

5 * (4 * (3 * (2 * (1 * factorial(0))))) // factorial(1) is added to call stack

5 * (4 * (3 * (2 * (1 * 1)))) // factorial(0) returns 1 to factorial(1)

5 * (4 * (3 * (2 * 1))) // factorial(1) return 1 * factorial(0) = 1 to factorial(2)

5 * (4 * (3 * 2)) // factorial(2) return 2 * factorial(1) = 2 to factorial(3)

5 * (4 * 6) // factorial(3) return 3 * factorial(2) = 6 to factorial(4)

5 * 24 // factorial(4) returns 4 * factorial(3) = 24 to factorial(5)

120 // factorial(5) returns 5 * factorial(4) = 120 to global execution contextFor n = 5, the evaluation of the factorial function involves 6 recursive calls to the factorial function including the base case.

While the basic recursive approach expresses the factorial function more closely with its definition (and more naturally) compared with the iterative approach, it also uses more memory as each function call is pushed to the call stack as a stack frame and popped off the call stack when the function call returns a value.

For larger values of n, the recursion gets deeper with more function calls to itself and more space has to be allocated to the call stack. When the space needed to store the function calls exceeds the capacity for the call stack, a stack overflow occurs!

To prevent infinite recursion from causing stack overflow and crashing the program, some optimizations have to be made to the recursive function in order to reduce consumption of stack frames in the call stack. A possible approach in optimizing the recursive function is by rewriting it as a tail recursive function.

A tail recursive function calls itself recursively and does not perform any computation after the recursive call returns. A function call is a tail call when it does nothing other than returning the value of the function call.

In functional programming languages such as Scala, tail-call optimization is typically included in the compiler to identify tail calls and compile the recursion to iterative loops that do not consume stack frames for each iteration. In fact, the stack frame can be reused for both the recursion function and the function being called within the recursion function [1].

With this optimization, the space performance for the recursion function can be reduced from O(N) to O(1) - from one stack frame per call to one stack frame for all calls [8]. In a way, a tail recursive function is a form of “functional iteration” with comparative performance to a loop.

For example, the factorial function can be expressed in the form of a tail recursion in Scala:

def factorialTailRec(n: Int): Long = {

def fact(n: Int, product: Long): Long = {

if (n <= 0) product

else fact(n-1, n * product)

}

fact(n, 1)

}While tail-call optimization is automatically performed during compilation in Scala, it is not the case for Python. Moreover, there is a recursion limit in Python (the default value is 1000) as a prevention measure against an overflow of the C call stack for the CPython implementation.

In this post, we learn about:

- Function composition

- Higher-Order Functions as a key implication of functional programming

- Recursion as a form of “functional iteration”

Have we found a replacement for “if-else” yet? Not entirely, but we now know how to write “loops” in functional programming using Higher-Order Functions and tail recursion.

In the next post, I will explore more on Higher-Order Functions and how they can be used in designing functional data pipelines.

Want more behind-the-scenes articles on my learning journey as a data professional? Check out my website at https://ongchinhwee.me!

- Functional Programming in Scala by Paul Chiusano and Rúnar Bjarnason

- Functional Programming Simplified by Alvin Alexander

- Functional Python Programming by Steven F. Lott, 2nd Edition

- Built-in Functions - Python 3.9.6 Documentation

- Scala Standard Library 2.13.6 - scala.collections.Iterable

- Trait Iterable | Collections | Scala Documentation

- tpolecat - The Point of No Return

- Don’t Use Return in Scala? - Question - Scala Users

- Tail Recursion - Functional Programming in OCaml

20

![[g \circ f \neq f \circ g]](https://res.cloudinary.com/practicaldev/image/fetch/s--HyEkpVh8--/c_limit%2Cf_auto%2Cfl_progressive%2Cq_auto%2Cw_880/https://latex.codecogs.com/svg.latex%3Fg%26space%3B%255Ccirc%26space%3Bf%26space%3B%255Cneq%26space%3Bf%26space%3B%255Ccirc%26space%3Bg)