26

How We are Making a Video Game in Python #3

This is the third edition in the series in which I will be going over game design in Python. This series will include guides to the key concepts of programming (Which was in the previous article!), as well as guides to OpenGL programming, Python GUI manipulation with Pygame and the problems and solutions that were faced in the making of Pycraft. For anyone unfamiliar:

Pycraft, a 3D open-source open-world video game made in python with Pygame, Numpy and PyOpenGL.

This article, released at the start of every month will document what changes have been made to the project, what challenges we faced and how we overcame them and how and where you can install this project from. For anyone wondering, this is to accompany the Pycraft weekly updates released weekly on Friday on my twitter page (@pycraftdev

on twitter: twitter.com/PycraftDev), under the #PycraftTJ. I am Tom Jebbo, the lead developer and graphics designer and I hope you enjoy both playing the game and reading this article!

An Introduction to Pygame

How to Create a Basic Pygame Display

Pygame GUI Design Techniques

Creating a Scrolling Text Effect with Scrollbar in Pygame

Pygame Graphs

How does all this Relate to Pycraft?

Time for some Updates to Pycraft

Final Words

Links and Credits

How to Create a Basic Pygame Display

Pygame GUI Design Techniques

Creating a Scrolling Text Effect with Scrollbar in Pygame

Pygame Graphs

How does all this Relate to Pycraft?

Time for some Updates to Pycraft

Final Words

Links and Credits

Pygame is a set of Python modules, based on the SDL library, that is designed for creating and manipulating windows in Python. For anyone unfamiliar the SDL library (or Simple DirectMedia Layer Library) is a multiplatform tool used widely in games to help with features such as; window creation, mouse and keyboard and joystick interactions, and directly connects to software like OpenGL to simplify development of games and other applications.

The library is widely supported on Windows, Mac OS, Linux, iOS and Android, which makes it a very popular tool simply because of its cross-platform support. Pycraft, the game I am developing is written entirely in Python, however modules like Pygame do interface and involve an amount of C, C++ and C# wrapping, however this is unavoidable.

So now I’ve explained what the SDL library is, what does it have to do with Pygame?

Well, Pygame uses SDL to directly communicate with your OS to detect and support the features and more mentioned above, however don’t confuse Pygame as a wrapper.

A wrapper is a program used to convert one program written in a different language to the one natively used by the developer, for example PyOpenGL (The wrapper we are using for OpenGL support in Python. This directly allows us to program using the same syntaxes and keywords as the program would in its native language, in OpenGL’s case that’s C, which would not normally work by default in Python.)

Pygame is not a wrapper because although it does interface with the C based SDL library, it also includes features written directly in Python. Pygame also enjoys the same multi-operating system support as SDL.

Now, if you’ve already used Pygame before then you might have a slightly different method of doing this, but this is the simplest method to create a window and control it in my testing.

We shall start by importing Pygame and initialising the module in a new Python window:

We shall start by importing Pygame and initialising the module in a new Python window:

import pygame

pygame.init()We must initiate Pygame, as this allows it to setup some of its internal Python syntaxes, like loading music, much in the same way when creating a class in Python you might when creating a class, create an init or init() subroutine that initiates variables and/or imports modules the class needs.

Next, we create our display, to do this we use the following syntax:

display = pygame.display.set_mode((1280, 720))Now let me just go through and explain what this line of code does, first of all we are creating a display 1280x720 pixels in width and height (where width goes first and height follows), and the name of our display is simply “display”, if you don’t assign your window a name it will default to that name. We define the dimensions of our display in double brackets here because we can add arguments like the example shown below to greater customise our display:

display = pygame.display.set_mode((1280, 720) DOUBLEBUF|OPENGL)That line of code might seem daunting at first, but expect to see more of that in a later article going over OpenGL in Python with Pygame, as we will need that then. But in short, we are defining two keywords here, DOUBLEBUF and OPENGL, which tell the display to load slightly differently to allow 3D rendering and framebuffers, which will be explained in that later article on OpenGL in Python and Pygame.

Moving on then, we now create a variable called clock, this is helpful because it will shorten our calls to Pygame’s clock function considerably later on making the code a bit more readable and easier to debug should we need to later, so, to do this we must write the following:

clock = pygame.time.Clock()And that’s everything outside of the game loop. If we were to run the project we have at this point if you want. We should get a black window pop-up, this window won’t do too much, and it’s very difficult to close, to do this we open task manager and locate our Python window (Called “Pygame window”, with the icon of a small snake holding a game console in its mouth) and click end task in the bottom right of the display.

Now as we can see, this isn’t very useful, so now we must create a game loop, this is a while loop that will run all the time the game runs, and everything we want out Python game to do, we specify here, from setting the display colour using:

display.fill([255, 255, 255])This code takes the name of the display, to get this we must check what we defined our display variable earlier and the colour values must be defined as a ‘rect style object’ (meaning that it must be defined as a python array so presumably Pygame can iterate over the colour values internally to set the display colours. We are using 0–255 colour values here, and for more information on this, and a handy colour picker, we recommend w3scools’s HTML colour picker, here: www.w3schools.com/colors/colors_picker.asp (and in this example we are setting our display colour to white).

This method is frequently used at the start of the game loop as this clears all the previous data drawn and rendered to the window, meaning you don’t get strange behaviour when moving objects around the display.

Next, we are going to create a for loop that will be detecting events to the window, and allow us to start making events that happen on different keypresses. We also use this to detect when we are trying to close the Pygame window, allow me to show you:

for event in pygame.event.get():

if event.type == pygame.QUIT:

quit()This simple for loop tells Pygame to give it all the events that have happened to the window single it was last called, so this also means we only call this once per game loop. We are storing the result of this call -so all the events that have occurred- in the variable ‘event’. Then below this we are checking what the type the event was, there are a few different types:

pygame.QUIT

pygame.ACTIVEEVENT

pygame.KEYDOWN

pygame.KEYUP

pygame.MOUSEMOTION

pygame.MOUSEBUTTONUP

pygame.MOUSEBUTTONDOWN

pygame.JOYAXISMOTION

pygame.JOYBALLMOTION

pygame.JOYHATMOTION

pygame.JOYBUTTONUP

pygame.JOYBUTTONDOWN

pygame.VIDEOEXPOSE

pygame.VIDEORESIZE

pygame.USEREVENTNow each of these event types also have even more sub-categories, for example you can use ‘pygame.KEYDOWN’ to detect key presses, and then use a nested if statement checking if ‘event.key’ is equal to ‘pygame.K_ID’ where ID is a placeholder for any key. You can get more information on this topic at Pygame’s documentation here: www.pygame.org/docs/ref/event.html Pygame is a really powerful too, as we can see, and I can’t go over every single possible function, there is plenty more to explore in this part alone!

Now because we have called ‘pygame.event.get()’ in our game loop our OS will know that the window is responding.

We have now told our display to set its colour to white in the example I’ve shown, but why Isn’t the display changing colour? To do this we need to update the display, to do this we can use two methods:

pygame.display.update()or

pygame.display.flip()Both syntaxes do update the display, but flip allows us to customise the area of the display that we are updating, and is supported better with some environments like OpenGL, but we don’t need to worry about that too much here, feel free to use either interchangeably, but only at the bottom of the event loop!

Now this is us complete, our display will now open to a specified size, enter a game loop, clear any previous drawings from the window, accept events like when we try to close it, and also update. And Pygame is really efficient, the game loop can run really quick… but hang on we don’t ever let our game loop run for long periods of time without slowing it down slightly, this may seem slightly counter-intuitive, but we really don’t need our program to refresh the display over 30,000 times a second. It’s bad for our PC temperature, performance and a waste of processing time. We can however limit our FPS to a set amount using the following syntax (using the clock variable we created earlier):

clock.tick(60)This limits our FPS to 60. We call this after we have updated our display.

So, now I have talked you through creating a simple display in Pygame, this code is the basis of the rest of the examples, and the basis of the GUI mechanics in my game Pycraft.

Here is the full code:

import pygame

pygame.init()

display = pygame.display.set_mode((1280, 720))

clock = pygame.time.Clock()

while True:

display.fill([255, 255, 255])

for event in pygame.event.get():

if event.type == pygame.QUIT:

quit()

pygame.display.flip()

clock.tick(60)

Below are a few methods to create effects in Pygame shown in Pycraft, based on the simple graphics program above.

In order to follow these instructions, you need only a small amount of experience in programming (ideally in Python, and using Pygame), and remember, this tutorial uses the previous GUI program as a starting point.

Let’s start with a bit of theory, Pygame renders a window, we will call this area the ‘window’, and we will call both the area we can and can’t see as the ‘frame’. If we have something we can’t fit entirely in the window, we can continue to render down below the frame, (remember; the top left-hand side of the frame is (0,0), and as we go down and right both coordinates increase.)

Let’s make an example, here we are loading a font (the system default) at size 30, and rendering ‘Some Text’, anti-aliasing it and setting the font colour to black (so we can see it on our white frame). For more information on font and loading text, I recommend you read the Pygame documentation here: www.pygame.org/docs/ref/font.html then we are rendering our text at position (0,0) on our display:

import pygame

pygame.init()

display = pygame.display.set_mode((1280, 720))

clock = pygame.time.Clock()

Font = pygame.font.SysFont("Arial", 30)

while True:

sampleText = Font.render("Some Text", True, (0, 0, 0))

display.fill([255, 255, 255])

for event in pygame.event.get():

if event.type == pygame.QUIT:

quit()

display.blit(sampleText, (0, 0))

clock.tick(60)

pygame.display.update()Now we need to allow the user to move the text up and down as if scrolling, to do this we need to first create a variable called “scroll”, this we will assign the value 0 at the beginning, this means we have moved ALL the objects on the display zero pixels up and down.

scroll = 0Then we need to do into the game loop, and then add a new event, we want to be able to increase and decrease the value of scroll when we use the scroll wheel on the mouse, we can use this code for that, building off our previous simple loop detection mechanism:

for event in pygame.event.get():

if event.type == pygame.QUIT:

quit()

if event.type == pygame.KEYDOWN:

if event.type == pygame.K_DOWN:

scroll += 5

elif event.key == pygame.K_UP:

scroll -= 5And finally, we need to add the value of the variable scroll to where we are rendering our text to the screen, in a larger solution we would do this for every text, shape and image that we plan on moving. This is how we will do this in our example:

display.blit(sampleText, (0, 0+scroll))Now, if we run the code, we can now use the arrow keys to move the text up and down, however, we have an issue, what if the user scrolls too far in one direction and loses their position. This next step is also really important for defining how large your frame should be in height, which we will need to know later for when we create our scroll bar. We can limit how far up and down the user can scroll by using the following lines of code in our game loop:

if scroll <= 0:

scroll = 0

elif scroll >= 100:

scroll = 100And now the result is a much easier to navigate display, please note that the minimum value should always be zero unless for some reason you want the user to be able to scroll upwards when the program first runs, which isn’t normally recommended as the user may not know to do this, but depending on your scenario you may want the user to scroll down more. And one more thing to note here is that the maximum value of scroll (which in our example is 100) does not mean the user can only scroll down 100 pixels on the window, it means there are 100 pixels below the window in the frame that the user can scroll to.

So now we have scrollable text in our GUI, and have prevented the user from essentially loosing themselves by going too high or low in the frame, but how do we tell the user that they can scroll down to see more information, and how far they can scroll? Well, we can use a scrollbar, like the one on the right-hand side of this article. To do this, we must use Pygame to create a rectangle:

We start creating our rectangle by defining its dimensions in a Pygame function, and give our rectangle variable a name:

Rect = pygame.Rect(1270, 5+scroll, 5, (720-(130/820)*720))In this line of code, we are defining the dimensions of a rectangle using the Pygame function ‘pygame.Rect’, this is part of Pygame’s drawing function which you can read more about here: www.pygame.org/docs/ref/draw.html And this function takes the following values in the following order:

The X and Y position on the display for the upper left-hand corner of the rectangle, then we add the values of the width and height to the rectangle.

In our example, on the X axis, we want the rectangle to be drawn on the right most side of the display, so because our display is 1280 pixels wide, drawing the rectangle at position 1270, gives us enough space to draw the rectangle and leave some space either side of the rectangle. On the Y axis we are drawing the rectangle starting at 5 pixels below the top of the display, and also displacing it with the value of scroll, this is important as we want the scroll bar to move with the window over the frame. Then we are defining the width, here we are creating a rectangle 5 pixels wide, but you can customise this. And the height, this bit looks the most complex, but it’s not too bad, let me explain; in an ideal scenario, we want to get a percentage of the frame visible in the window, remembering that the height of the window is 720 and we allowed the user to scroll 100 pixels below this, so the height of the frame is 820 pixels, and we get 130 because this program was made on Windows 11, and we don’t want to lose some visibility of the scroll bar because of the new rounded corner window design. And finally, we also need to take that percentage away from 720, the height of the display otherwise the rectangle would be inverted.

Then we can draw our rectangle to the display by using the following syntax:

pygame.draw.rect(display, (255, 0, 0), Rect)Where the display is the window or GUI open in Pygame, the second set of values in the tuple structure is the colour of the scrollbar, in this case its red because we wanted it to stand out, but you can change this to whatever values you wish, and finally we are specifying the rectangle which we just created.

And we are done; here is the full code for this:

import pygame

pygame.init()

display = pygame.display.set_mode((1280, 720))

clock = pygame.time.Clock()

scroll = 0

Font = pygame.font.SysFont("Arial", 30)

while True:

Rect = pygame.Rect(1270, 5+scroll, 5, (720-(130/820)*720))

sampleText = Font.render("Some Text", True, (0, 0, 0))

display.fill([255, 255, 255])

for event in pygame.event.get():

if event.type == pygame.QUIT:

quit()

if event.type == pygame.KEYDOWN:

if event.type == pygame.K_DOWN:

scroll += 5

elif event.key == pygame.K_UP:

scroll -= 5

if scroll <= 0:

scroll = 0

elif scroll >= 100:

scroll = 100

display.blit(sampleText, (0, 0+scroll))

pygame.draw.rect(display, (255, 0, 0), Rect)

clock.tick(60)

pygame.display.update()This is a demonstration of the scrollbar animation:

If you have seen the ‘Devmode’ functionality of my Python project, Pycraft, then you might be wondering how we are able to draw graphs representing different statistics, like for example FPS, memory usage, average FPS and CPU usage then allow me to show you.

First of all, we will be starting again with the original Pygame example shown at the start of this project, for this example we will also need some form of data collection, whilst I will not be going over how to collect data from your project, however I will point you in a good direction to start:

You can use a python module called Psutil, here: https://pypi.org/project/psutil, to collect CPU and memory and lots of system data (it also mentions thermals however it’s not well supported on a lot of devices from my experience), however GPU usage and information you can use GPUtil for that (here: https://pypi.org/project/GPUtil/), however it’s a much less simple process (and only supports Nvidia graphics cards). I would also recommend running metrics collection is a background thread on your project and communicating via global variables, it’s probably the one place I would recommend you use global variables. (However, if this is an area people want me to go into in greater depth, I’ll be happy to next month!)

Anyway, this project will require the data from system metrics to be in an iterable format, whether that’s a list or array (it can be a NumPy array), or even a string (however I would not recommend that), it really depends on your program and how you want to collect and organise your data. For this example, the data will be stored as a list.

We must start outside of the game loop program and create some form of counter variable, for this we will name our variable ‘Counter’ and because indexing in python starts at zero, we must set our variable also to zero.

Counter = 0Then we, still outside of our game loop need to also create an array, we will store this array in a new variable ‘Points’:

Points = []Next, we need to take the value from our iterable data we mentioned earlier, — for this I will be using a variable called ‘ExternalData’ which will not be defined in this program, this will be your array, or list or tuple of data you have collected from somewhere. — But what we need to do here, is append the most recent piece of data, as well as the ‘Counter’ we created in an array, with each point as a tuple; The ‘Counter’ will be our X position, so as the program runs the graph extends to the right, however using a negative number as ‘Counter’ will invert the X axis of the graph, moving it from Right to left, and of course you can switch the X and Y values for a similar effect as before, except this time we can make the graph extend up and down. Bear in mind if you decide to not use the method shown here, then you will need to add a constant to each value else it may go off the screen. So, we are adding this line of code to the start of our game loop.

Poins.append((Counter, ExternalData[Counter]))Now, we have got a system for creating points from our ‘Counter’ variable and our ‘ExternalData’, now we need to plot our data, to do this we must use the following syntax:

pygame.draw.aalines(display, (255,0,0), False, Points)This subroutine takes the display we created earlier, and a colour value (In this case we chode red for clarity), now the Boolean value here decides whether we want a line connecting our first and last point, as we don’t here, we can leave that as false, and finally we need to add our ‘Points’ variable, this tells Pygame where to draw points and lines.

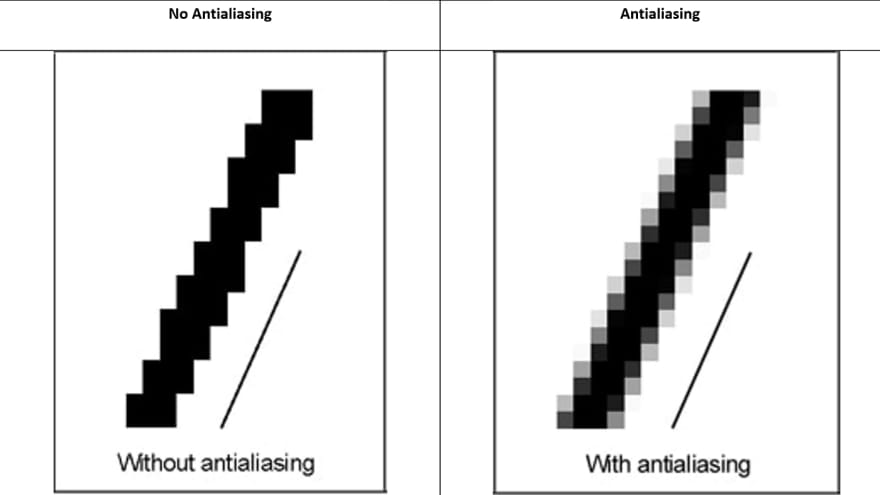

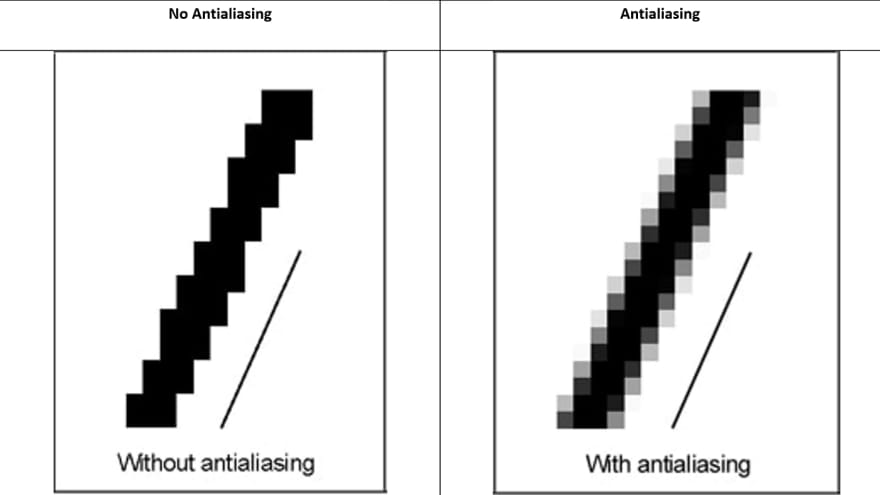

Let’s take a moment here to consider Pygame’s Nomenclature (Or Naming scheme) here; the function ‘pygame.draw’, has a few supported shapes, so far in this article we have looked at rectangles and now multi-point lines, if we wanted to simply draw a single line, with a start and end point, we would omit the ‘s’ on lines. The ‘aa’ at the start is a simple anti-alias option, and by including it we are telling Pygame to anti-alias our line.

For anyone unfamiliar, anti-aliasing is used to smooth out a diagonal line on a window, as our displays are simply a series of individually controlled rectangles, we can’t get inherently smooth diagonal lines, so by using this effect, we are changing the colours of the surrounding pixels to blend the line better. A good way to show this is with a diagram:

Then we need to enter the game loop, at the very bottom of the game loop we need to increment our counter by 1; like this:

Counter += 1Now, by now I’m sure a few of you are at this point wondering why we don’t do this in a for loop, now my reply to you there is this:

But also at this point, we can run the program, but it will not work, we need to add one more final thing, because Pygame’s ‘pygame.draw.aalines’ function, or ‘pygame.draw.lines’ function require multiple points, we need to let the program run at least twice first, as this allows us to have created our first and second point. To do this we need to add the following if statement to our code:

if Counter >= 2:This stops our code from crashing. And this is our code at this point in this example;

import pygame

pygame.init()

display = pygame.display.set_mode((1280, 720))

clock = pygame.time.Clock()

Counter = 0

Points = []

while True:

Points.append((Counter, ExternalData[Counter]))

display.fill([255, 255, 255])

for event in pygame.event.get():

if event.type == pygame.QUIT:

quit()

if Counter >= 2:

pygame.draw.aalines(display, (255,0,0), False, Points)

pygame.display.flip()

clock.tick(60)

Counter += 1But I’d like to mention a few things you may need to remember if following this example:

if Counter >= 100:

Counter = 0(Where 100 is the maximum value, the variable can take (and by relation the maximum X position the graph can draw to).

So, when we run this program now, we will all get different results, this is because we all are using different ‘ExternalData’ variables. Here are a few examples, the first is just a simple flat line (the variable ‘ExternalData’ is given the value of 10 (not zero here because it’d be hard to see) and that value is repeated enough times for the line to be drawn across the display)

Well, these are all features shown in Pycraft and ones I’m often asked about, there are loads of other tricks we use in Pycraft to create effects like these, but those two were chosen because they were less documented online, and the harder ones to perfect.

Pycraft is a game I’m making in Python and this project is to push Pycraft and its modules to show what is possible, and as much as I’d like to move straight on to PyOpenGL and how we are making that, I need to first actually make progress on the project, and by writing these articles it might be helpful to see my methods of programming, because when we get onto OpenGL, things will get really difficult and I want to make sure everyone is familiar with using Python and Pygame first, so this will appeal to both beginners and masters of Python. And I want to make these tutorials on Pycraft as a whole and not just the game engine, because there were lots of other issues and challenges, we faced elsewhere to get to where Pycraft is today, and where Pycraft will be in the future.

In my last article here: https://medium.com/@PycraftDev/how-we-are-making-a-video-game-in-python-2-547b504bbd67 we looked at the development time-line of Pycraft and where the project is heading, and there are a few updates I’d like to make, and news to share.

First of all, an installer has been made in Tkinter, this project will be used in a future plan for Pycraft v0.9.2 to keep Pycraft up-to-date over all es (executable, raw Python and PyPi editions), because the version ID given to the projects released on PyPi are the same as on every other version of Pycraft, and as such if there is an update, Pipi’s package pip can be used to detect out of date software, and by a stretch if Pycraft is out of date. There is a whole lot more testing that needs to go here to make sure it’s all feasible, but that’s an additional feature coming to Pycraft v0.9.2.

I’m sure now you’re all wondering ‘when was Pycraft on PyPi?’ And I’m proud to announce that around the time of Pycraft’s 3-year anniversary on the 1st of November, Pycraft went into testing on Pypi, and now that everything is sorted out it is live, and has been for a few days now (I posted the news on my twitter page here: https://twitter.com/PycraftDev). This provides a new, easier way to get Pycraft up and running. Pycraft can now be downloaded using the following syntax in the same way you downloaded Pygame:

pip install Python-Pycraft

Pycraft v0.9.2 will, in addition to the new installer, also support multiple languages, I’ve not planned which ones yet, but at a stretch definitely most European and Asian languages will be supported, but this will absolutely increase and improve as future updates are rolled out. And that language support goes for all of Pycraft, the new installer, all the GitHub pages and will include everything added in the future where possible.

Now let’s focus on some of the changes coming to Pycraft in Pycraft v0.9.1, a feature really handy for me, and fellow statisticians and beta-testers, the graphs for Pycraft’s ‘Devmode’, have been reprogrammed (like the ones mentioned earlier), simplifying the process and improving especially when displaying the CPU usage. In addition, it’s time for one of the most exciting changes coming to Pycraft v0.9.1, Vertex Buffer Objects (or VBO’s).

This is something that has been a big issue for me in Pycraft and is one of the main reasons why the game engine hasn’t improved much in the past few updates, because Python wasn’t fast enough iterating over the relatively small number of vertices in the map, but now because of VBO’s, which will likely have an entire article dedicated to alone, we can have a higher poly map, characters, plants and animals and structures in the game, which is exactly what will be added in the following Pycraft v0.9.n updates, as well as better collisions. However, this update would not be possible without the help from https://twitter.com/DmitryChunikhin!

Thank you for reading this article, I hope that you have liked this article and hopefully you have learned a few Pygame tricks and caught up will all things Pycraft. If you want to share this article that would be greatly appreciated!

Pycraft v0.9 and Pycraft v0.9.1 took a very long time to develop, and a lot of work was put into both that update, Pycraft as a whole and writing these articles for you, as a result if you have any questions feel free to message me here on twitter (https://twitter.com/PycraftDev) or drop me an email at (ThomasJebbo@gmail.com).

I’m regularly on Twitter so feel free to message me with any questions you may have on the project, for feel free to let me know of any typos and mistakes!

Thank you for reading this article, that’s really appreciated. And remember; anyone can learn to code. And games like my own, which I’m still working on, from a programming point of view are possible for everyone!

My Twitter Page: https://twitter.com/PycraftDev

My GitHub page: https://github.com/PycraftDeveloper

Pycraft can be found here: https://github.com/PycraftDeveloper/Pycraft

Pycraft can be also found here: https://pypi.org/project/Python-Pycraft/

My GitHub page: https://github.com/PycraftDeveloper

Pycraft can be found here: https://github.com/PycraftDeveloper/Pycraft

Pycraft can be also found here: https://pypi.org/project/Python-Pycraft/

Pygame (www.pygame.org), Numpy (numpy.org), Pillow (PIL) (python-pillow.org), Python (www.python.org), Tkinter, PyAutoGUI (pyautogui.readthedocs.io/en/latest), psutil (psutil.readthedocs.io/en/latest), GitHub (github.com), PyOpenGL (PyOpenGL — The Python OpenGL Binding (sourceforge.net)), OpenGL (www.opengl.org), YouTube, Windows, Visual Studio Code (code.visualstudio.com), Microsoft and My amazing Twitter followers and community.

This edition, and future editions of this series will not be including images of code, although this can look nicer and syntax highlighting can be helpful, having code written out here makes it friendly for those in the development community who have sight issues (like myself), or if you want to have this article read to you!

Please note links under the “With thanks to” are not moderated by me, they are safe links at the time of writing however I do not control the content on them.

26